Our chapter on national security and foreign policy mentions that a number of organizations make up the intelligence community. One is the

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. If you haven't heard of it, don't feel bad. At one point, President Obama was unfamiliar with it,

as Mark Ambinder reported last year:

President Obama's first brush with the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency was ignominious. Out for lunch in May 2009, at a Five Guys burger franchise in Washington, the new President started to shake the hands of other customers, TV cameras in tow. Then he turned to men with government ID badges.

"So what do you?" the president asked. "I work for at NGA, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency," one said.

"Outstanding. How long have you been doing that?" Obama wondered. "Six years." Obama then asked: "So, explain to me exactly what this National Geospatial..." His voice trailed off. "Uh, we work with, uh, satellite imagery." Obama: "Sounds like good work." The response is obscured by the audio.

Suffice it to say: Obama knows what the NGA does today.

Any number of officials and agencies have been in the limelight since the raid on Osama bin Laden, including the CIA and the Defense Department. But the little-known and little-heralded work of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, often called the NGA, was central to the demise of the terrorist leader.

The NGA integrates several core intelligence functions. It makes maps and interprets imagery from satellites and drones; it also exploits the electromagnetic spectrum to track terrorists and decipher signatures off of enemy radar.

Fifty years ago today, its predecessor organization, the National Photographic Interpretation Center, played a major part in the Cuban Missile Crisis. It analyzed

U-2 images from the day before, concluding that the

Soviet Union had placed

offensive missiles in Cuba.

NGA picks up the story:

This imagery was key to understanding that the Soviet intentions in Cuba were more threatening than previously assessed. Until these images, captured by Air Force U-2 high altitude and U.S. Navy low altitude photo reconnaissance aircraft, only defensive weapons – surface-to-air missiles – had been detected by U.S. intelligence, which seemed to support statements made by Khrushchev.

A team of imagery analysts under the leadership of National Photographic Interpretation Center founding director Arthur P. Lundahl pored over these images, quickly realizing the gravity of their discovery and the risk they posed to upsetting the balance of power between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Analysts Dino Brugioni, James Holmes, Vincent DiRenzo Dick Reninger and Joseph Sullivan worked to prepare Lundahl to brief then-President John F. Kennedy the next day, leading to the crisis.

From the

National Security Archive at George Washington University:

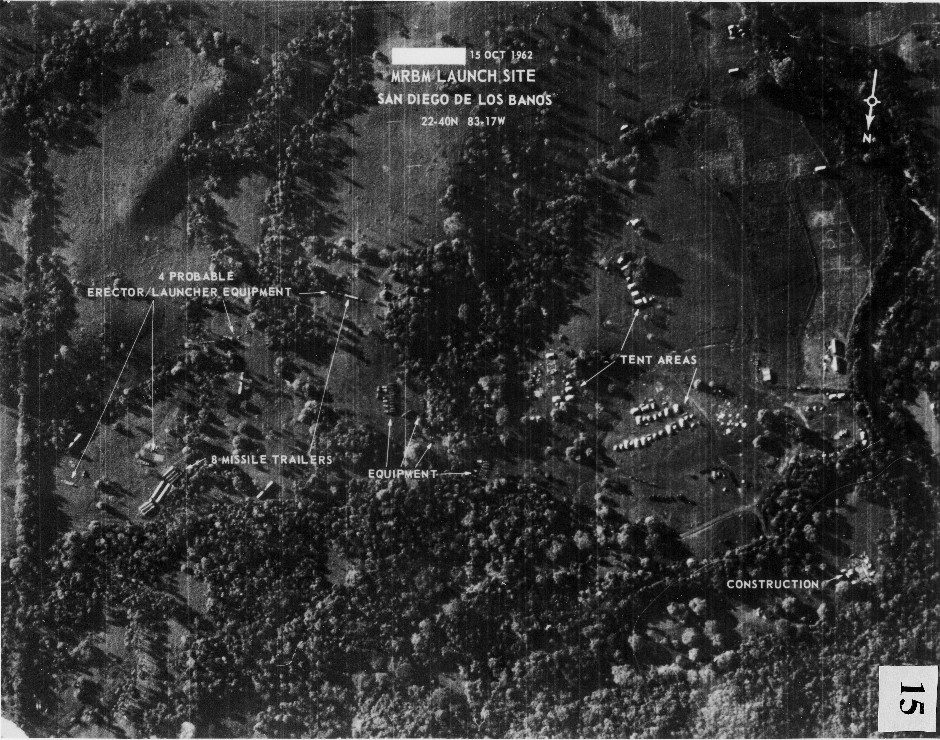

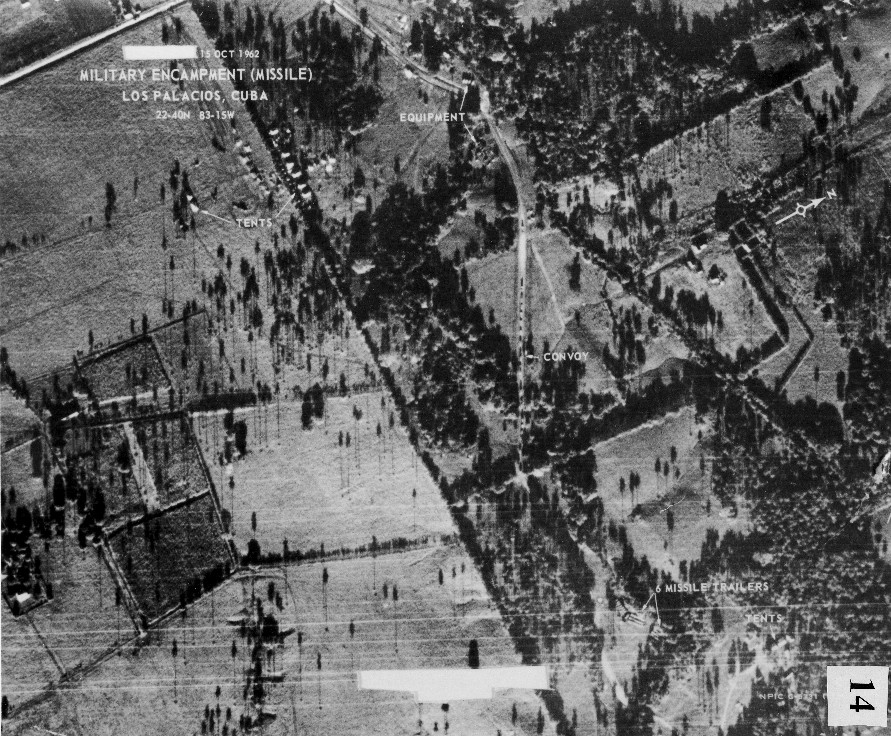

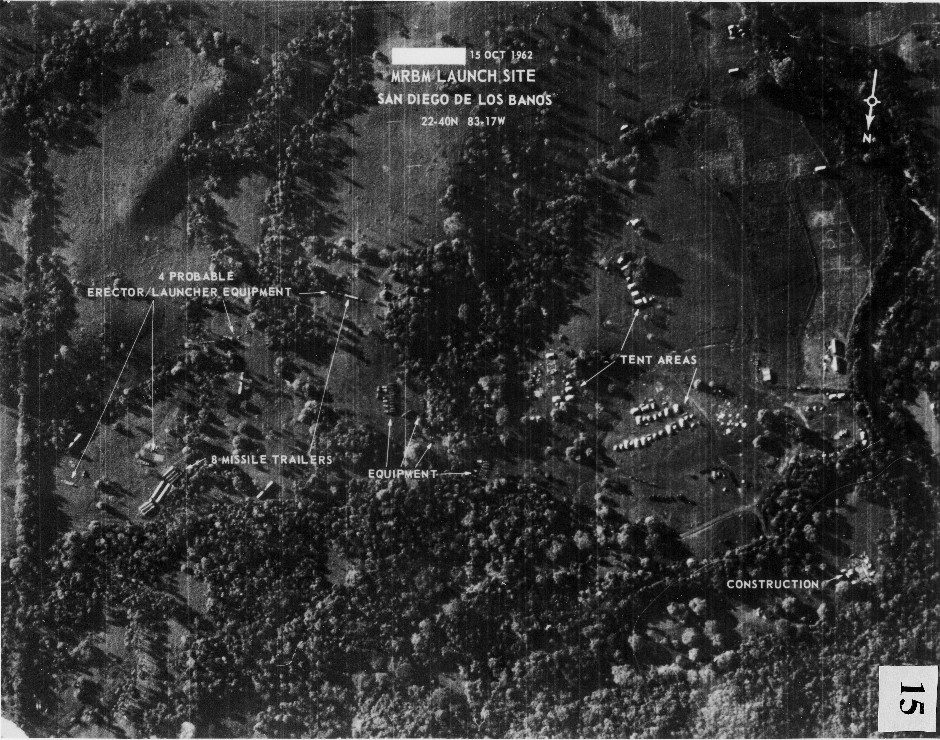

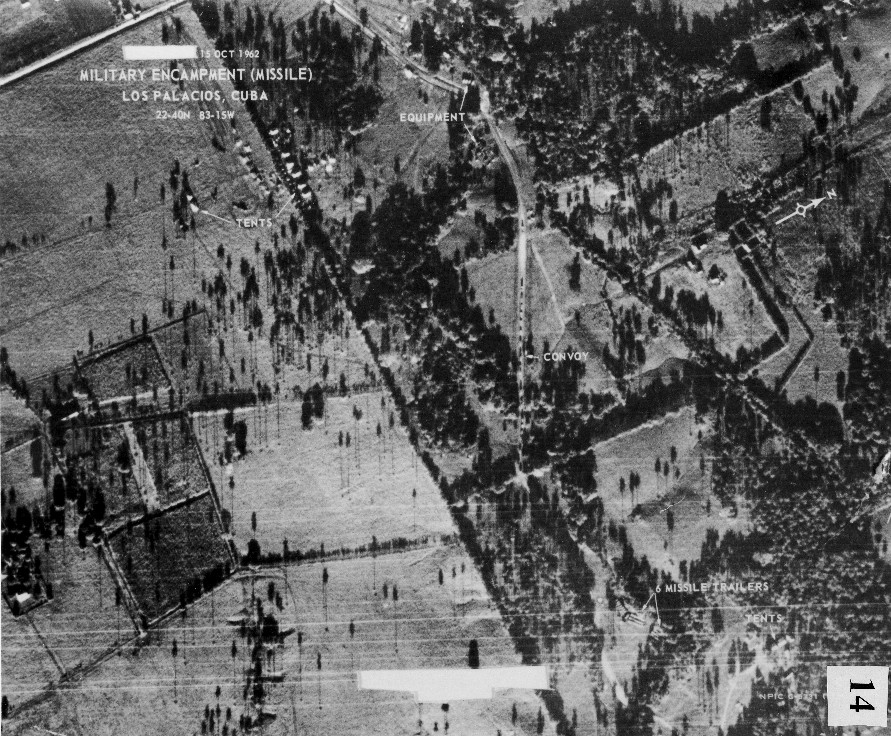

October 14, 1962: U-2 photograph of a truck convoy approaching a deployment of Soviet MRBMs near Los Palacios at San Cristobal. This photograph was the first one identified by NPIC on 15 October as showing Soviet medium-range ballistic missiles in Cuba.

October 14, 1962: U-2 photograph of MRBM site two nautical miles away from the Los Palacios deployment – the second set of MRBMs found in Cuba. This site was subsequently named San Cristobal no. 1 (the photo is labeled 15 October for the day it was analyzed and printed).